Royal Park by Night

Royal Park comes alive after dark.

Most Australian mammals (70%) are nocturnal, and greater than 60% of insects are active at night.

Did you know that Royal Park is a designated “Dark Park” keeping all external lights to the bare minimum in order to protect and maintain a healthy wildlife population.

For Biodiversity to thrive, both plants and animals depend on Earth’s daily cycle of light and dark to govern life-sustaining behaviors such as reproduction, nourishment, sleep, protection from predators and preventing dehydration from the heat of the day.

Diurnal (Daylight ) animals are usually active during daylight and rest when its dark.

Crepuscular (Twilight) animals are most active in the early morning and late evening and rest at other times.

Nocturnal (Night) animals are active during the night when it’s totally dark and rest during other times of the day.

Artificial light effects our 24 hour circadian rhythms, hormones and melatonin levels. It disrupts the health and wellbeing of humans, and wildlife alike.

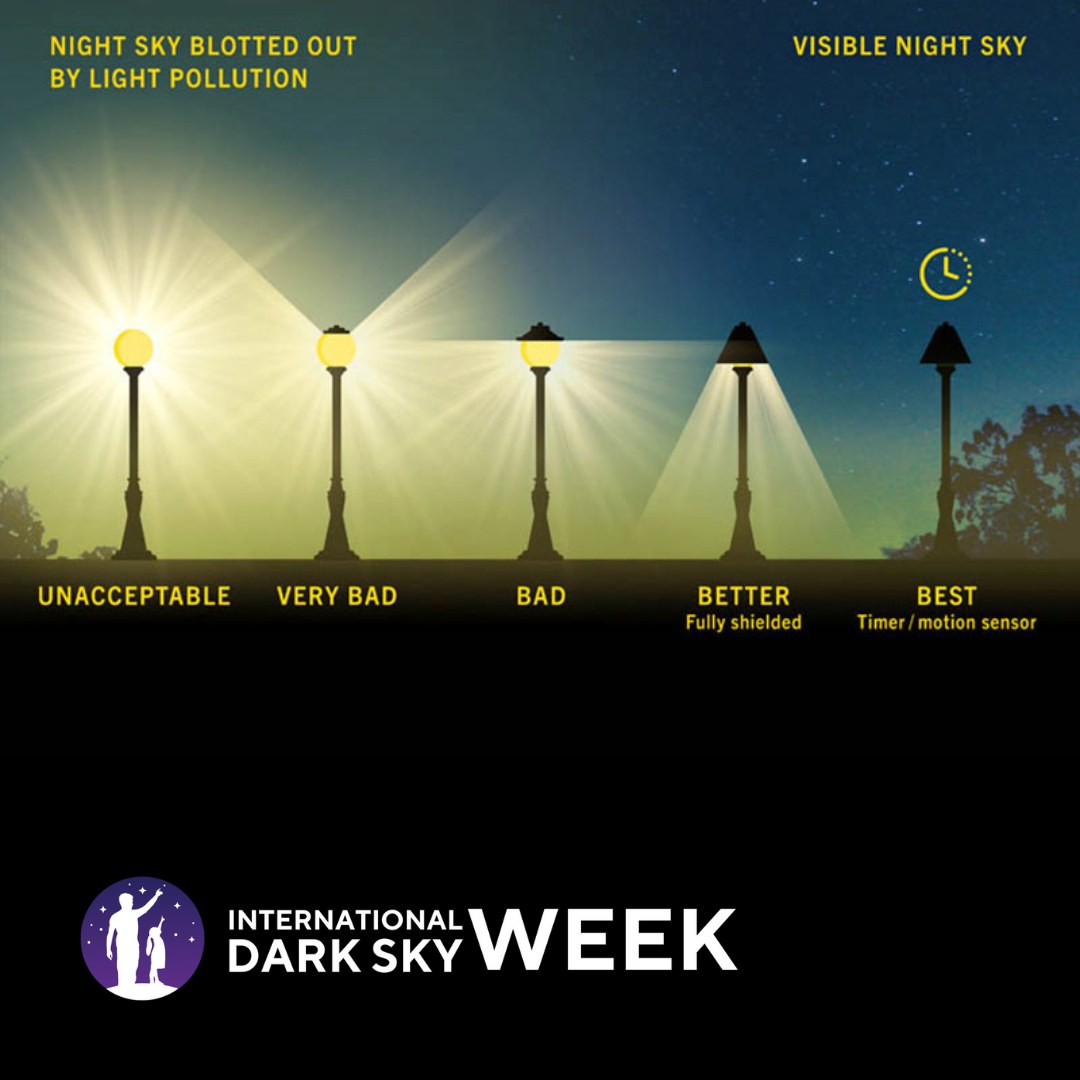

How bad is light pollution?

With much of the Earth’s population living under light-polluted skies, overlighting is an International concern. If you live in the city or the suburbs, you may have noticed the amount of sky glow and low amount of visible stars, especially compared to what you’d find in regional areas. This wasn’t always the case.

“Light pollution is increasing by 10% year on year, it is the fastest growing pollutant in the world” , Australian Dark Sky Alliance.

According to the 2016 groundbreaking “World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness,” 80 percent of the world’s population lives under sky glow. In the United States and Europe, 99 percent of the public can’t experience a natural night.

Lights at night are perceived as enhancing safety as people feel safer, however research is proving this to be complicated:

Public lighting, LEDs and safety: it’s complicated :: ECD (Electrical+Comms+Data) (ecdonline.com.au)

Meet some of our Royal Park residents that need and only come out when it's dark

Australian Microbats

What Species of Microbats can be found in Royal Park ?

Natural Pest Controllers.

Insect eating bats belong to a group of bats called ‘microbats’ which find their way through the dark by using ‘echolocation’, listening to the echoes from their high frequency calls. These calls are usually well above the range of human hearing , but some species like the White-striped Freetail Bat can be heard by humans.

Microbats can eat as much as 40% of their own body weight of insects in a single night or several hundred insects per hour.

The composition of insects consumed by bats varies between species.

The Little Forest Bat consumes bugs, beetles, moths, ants, flies and mosquitoes. The Chocolate Wattled Bat has been recorded feeding almost entirely on moths. The Southern Freetail Bat has been recorded feeding on bugs, ants, flies and mosquitoes.

They can slow their bodies down and go into torpor to save energy when it is cold or when they’re inactive during the day. In this state they are quite vulnerable. They can live a very long time for such small animals, sometimes more than 30 years, but usually less than this.

In Victoria, there are 18 species of microbats dependent on tree hollows. Both dead and live trees with hollows are critically important for these hollow roosting bats.

If you like the idea of mosquitoes being eaten by the thousands, cheer on a Microbat.

If you find a microbat in trouble, do not touch it, but call Microbats of Melbourne, a licensed DEECA Wildlife shelter ph:0407 636 688 for help/ advice

Australian Megabats

Mega Bats, Mega Pollinators.

Flying foxes (also known as fruit bats) are the largest bats in Australia. They use night vision and sense of smell instead of echolocation to navigate (their night vision is as good as a cat) They feed on fruit and blossoms rather than insects, and they roost in large groups called camps, hanging in tree branches rather than in caves or tree hollows.

All flying foxes are protected by law in Australia. Spectacled and Grey-headed Flying fox populations have suffered dramatic declines, due to destruction of feeding habitat, heat stress and fruit net entanglement, and they are now listed as vulnerable to extinction under environment laws.

Flying foxes feed in the forest canopy and eat a diverse range of plants. For example, Grey-headed Flying foxes eat fruit from over 50 species of rainforest trees and vines, blossoms from nearly 60 species of eucalypts, melaleucas and banksias, and various introduced and cultivated fruits.

Flying foxes provide essential services to these plants and forest ecosystems, by pollinating flowers and dispersing seeds into the forest over many kilometers.

The flowering patterns of most eucalypts are irregular and erratic. As a result, the distribution of feeding areas for flying foxes varies substantially from year to year and from place to place. Australia’s flying foxes are remarkably adept at tracking food over long distances and the migration paths of individuals vary widely as do the distances they travel up the Eastern coast of Australia.

Some Grey-headed Flying foxes have been tracked moving 500 km in 48 hrs, whereas others live in a single camp for many years. Many flying-foxes have a long-distance, nomadic lifestyle, feeding on a wide range of plants in hundreds of forest types as they travel across the Australian landscape.

If you like forest trees repopulated after fires, droughts, or deforestation, cheer on a Megabat.

If you see a Flying Fox in trouble, do not touch it but please SMS : 0409 530 541 Fly By Night, a licensed DEECA Wildlife shelter in Melbourne for help / advice.

Melbourne Injured Flying Fox & Bat Rescue – Fly By Night Bat Clinic Inc

Saving our bat babies – Australian Geographic

Any netting used to protect household fruit-trees, vegetable gardens, or other fruiting plants must have a mesh size, of 5mm x 5mm or less at full stretch. As a guide you should not be able to poke your finger through the netting.

This new mandatory requirement was introduced under Victoria’s Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulations 2019 (POCTA Regulations). Any existing household fruit netting that does not meet this specification must be replaced with appropriate netting.

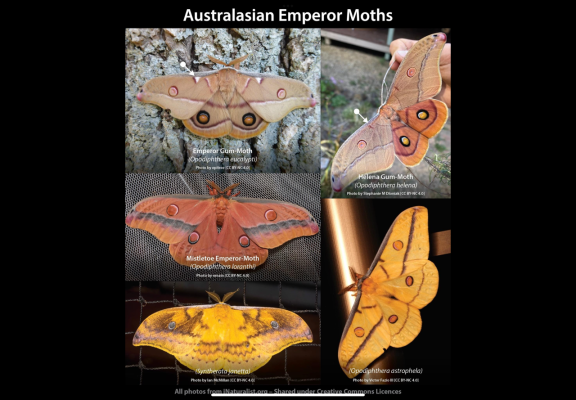

Australian Moths

Australian Butterflies and moths are in the Order Lepidoptera which means scaly wing. Australia has around 22,000 species of moths, only half of which have been scientifically described. There are only around 400 species of Butterflies.

Moths are a crucial part of the ecosystem. The caterpillar larvae eat plant material and transform it into animal protein. This is then a major food source for millions of birds, other invertebrates, mammals and reptiles. As caterpillars are heavily predated, they mostly feed at night when birds are inactive. Moths in their adult stage are also protein balls eaten by birds, bats, spiders, lizards and small mammals.

Bushland like Royal Park should be made up of 80% small bush birds. These small insectivorous birds will feed their chicks about 300 caterpillars and other insects each day. That is just one nest for one day. Most small birds fledge in 10-14 days.

Moths are also important pollinators, especially of plants that release scent at night like Stackhousia spp. Some species even eat decaying wood and dead leaf litter recyling the nutrients there.

Losing our moths would be Catastrophic : The Magic of Moths – Gardening Australia (abc.net.au)

Bright lights at night disrupt a moth’s normal behaviour (both adult and caterpillar) and allows them to be targeted by predators. Why are moths attracted to lights? Science may finally have cracked the case | Canada’s National Observer: Climate News

So in order to allow bats, birds, lizards, small mammals and other invertebrates to survive and raise their young, encourage more native plants in your gardens for the caterpillars, don’t use pesticides or herbicides and keep the outdoors dark.

Along with heat waves, insecticides, artificial lighting and loss of indigenous plants and habitat, European Wasps are a new threat to Moths and caterpillars. They eat protein and target caterpillars and other insects to feed their pupae.

If you notice European wasps in your garden, “European Wasp Control Project” on Facebook, describes some baiting stations for Wasp control.

Tawny Frogmouths

The Tawny Frogmouth is found throughout most of the Australian mainland, except in heavy rainforests and treeless deserts. They are large, long-lived birds, one captive bird in the London Zoo lasted to 32 years of age, although it appears 13 years of age in the wild is common. Frogmouths belong to the frogmouth genus Podargus, and although related to owls, their closest relatives are the owlet-nightjars and true nightjars.

Owls possess strong legs, powerful talons, and toes with a unique flexible joint they use to catch prey. Tawny Frogmouths prefer to catch their prey with their beaks and have fairly weak feet. Tawnys roost out in the open, relying on camouflage for defence, and build their nests in tree forks, whereas owls roost hidden in thick foliage and build their nests in tree hollows. Tawny Frogmouths have wide, forward-facing beaks for catching insects, whereas owls have narrow, downwards-facing beaks used to tear prey apart. The eyes of Tawny Frogmouths are to the side of the face, while the eyes of owls are fully forward on the face.

During the day, these birds perch themselves on low tree branches, cleverly mimicking the tree branch itself, perching upon it with its head inclined upwards at a distinctive angle camouflaging itself perfectly. They need large mature trees to breed as they nest on large horizontal branches. They form permanent partnerships often nesting in the same tree year after year. The leading edge of the first primary wing feathers are fringed to allow for silent flight.

The bulk of their diet is composed of large nocturnal insects, such as moths, as well as spiders, worms, slugs and snails, but also includes a variety of bugs, beetles, wasps, ants, centipedes, millipedes and scorpions. Large numbers of invertebrates are consumed to make up sufficient biomass. Small mammals, reptiles, frogs and birds are also eaten.

During winter, the food supply shrinks drastically, and prewinter body fat stores can only provide a limited supply of energy. Tawny Frogmouths are unable to survive the winter months without spending much of their days and nights in torpor. Torpor results in energy conservation by significantly slowing down heart rate and metabolism, which lowers body temperature. Torpor is different from hibernation in that it only lasts for relatively short periods of time, usually a few hours.

Large-scale land clearing of eucalypt trees and intense bushfires are serious threats to their populations, as they tend not to move to other areas if their homes are destroyed. House cats are the most significant introduced predator of the Tawny Frogmouth, but dogs and foxes are known to also occasionally kill the birds. When Tawny Frogmouths pounce to catch prey on the ground, they are slow to return to flight and vulnerable to attack from these predators.

As they have adapted to live in close proximity to humans, Tawny Frogmouths are at high risk of exposure to pesticides. Continued widespread use of insecticides and rodent poisons are hazardous as they remain in the system of the target animal and can be fatal to a Tawny Frogmouth that eats them. The effect of these toxins is often indirect, as they can be absorbed into fatty tissue with the bird experiencing no overt signs of ill health until the winter, when the fat deposits are drawn on and the poison enters the bloodstream.

Owls

Australia is home to eleven species that collectively cover every state and territory. From our smallest species the Australian Boobook, standing at 25 cm tall to our largest, the Powerful Owl at 65 cm, owls can be found in various habitats from wet rain forests to open woodlands.

In Royal Park we have two species listed in iNaturalist, the Barn Owl (Tyto alba) and the Australian Boobook (Ninox boobook)

The Australian Boobook is the smallest and most widespread owl. They have predominantly dark-brown plumage with prominent pale spots, and grey-green or yellow-green eyes. They give a double hoot (“boo-book” or mo-poke”), the second note generally lower in pitch than the first. The owl roosts in dense foliage or safely inside a tree hollow.

The Australian Boobook feeds on insects, small mammals and other small animal species. Most prey is detected by listening and watching from a suitable tall perch. Once detected, flying prey, such as moths and small bats, is seized in mid-air, while ground-dwelling prey is pounced upon.

The Barn Owl is the world’s most recognized owl. It is a medium-sized, pale-coloured owl with long wings, a ‘heart-shaped’ facial disc and a short, squarish tail. The barn owl does not hoot. They are generally quiet, the common call being a 12 second rough, hissing screech. Barn Owls feed mostly on small mammals, mainly rodents, and birds, but some insects, frogs and lizards are also eaten. One of the more favoured foods is the introduced House Mouse. Barn Owls hunt in flight, searching for prey on the ground using their exceptional hearing. The heart-shaped structure of the facial disc is unique to these types of owls (Tyto species). The slightest sound waves are channelled toward the ears, allowing the owl to pinpoint prey even in complete darkness

Nationally, the conservation status of all Australian owl species is ‘not in danger’. However, from state to state owls are facing their own problems due to two main issues. The first is baiting of prey items such as mice to stop agriculture and farming losses. The second, habitat loss, is a far bigger issue. Most of our owl species rely heavily on old growth trees with hollows for breeding. Hollows take hundreds of years to form and land clearing is wiping out these trees at an alarming rate.

Keeping Rat Poison out of the food chain – What to buy and avoid — Act for Birds

Possums

Royal Park has two species of possums:

The common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula, from the Greek for “furry tailed” and the Latin for “little fox”)

This nocturnal marsupial possum is up to the size of a small cat, with pointed ears and large fluffy black tail. The common brushtail possum can adapt to numerous kinds of vegetation but it is largely omnivorous. It prefers Eucalyptus leaves, but also eats flowers, shoots, fruits, and seeds. It may also consume animal matter such as insects, birds’ eggs and chicks, and other small vertebrates. Brushtails may eat three or four different plant species during a foraging trip. The brushtail possum cannot rely on Eucalyptus alone to provide sufficient protein.

They have a mostly solitary lifestyle, and individuals keep their distance with scent markings and vocalisations. They usually make their dens in natural places such as tree hollows and caves, but also use spaces in the roofs of houses. As with most marsupials, the female brushtail possum has a forward-opening, well-developed pouch. The chest of both sexes has a scent gland that emits a reddish secretion which stains that fur around it. It marks its territory with these secretions. In Australia, brushtail possums are threatened by humans, tiger quolls, dogs, foxes, cats, goannas, carpet snakes, and powerful owls. Brushtail possums also compete with each other and other animals for den spaces, and this contributes to their mortality.

Use this guide if you see a possum in trouble, by Wildlife Victoria

The common ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus peregrinus, Greek for “false hand”) is another Australian nocturnal marsupial.

The common ringtail possum is small, half the size of a small cat with rounded ears, and a long slender prehensile tail which normally displays a distinctive white tip over 25% of its length. It has grey or black fur with white patches behind the eyes and usually a cream-coloured belly.

It lives in a variety of habitats and eats a variety of leaves of both native and introduced plants, as well as flowers, fruits and sap. This possum also consumes caecotropes, which is material fermented in the caecum and expelled during the daytime when it is resting in a nest. When foraging, ringtail possums prefer young leaves over old ones. One study found the emergence of young possums from their pouches corresponds to the flowering and fruiting of the tea-tree, Leptospermum and the peak of fresh plant growth. Young eucalypt leaves are richer in nitrogen and have less dense cell walls than older leaves; however, the protein gained from them is less available due to higher amounts of tannins. It has been found that at higher temperatures, the common ringtail possum consumes less food due to a limited ability to metabolize toxins found in their diet.

Common ringtail possums live in their communal nests, called dreys. They build nests from tree branches and occasionally use tree hollows. A communal nest is made up of an adult female, an adult male, their dependant offspring and immature offspring of the previous year. A group of ringtail possums may build several dreys at different sites. Ringtail possums are territorial and will drive away any strange ringtails from their nests. A group has a strong attachment to their site. Ringtail possum nests tend to be more common in low scrub and less common in heavily timbered areas with little under-story. Dreys contribute to the survival of the young when they are no longer carried on their mother’s back

Because they are largely arboreal, common ringtail possums are particularly affected by deforestation and heat stress. They are also heavily preyed upon by the introduced red fox. They are also hit by cars, or killed by snakes, cats and dogs in suburban areas.

More Dark Sky Information:

Artificial Light at Night -State of the Science 2024

Environmental | ADSA (australasiandarkskyalliance.org)

International Dark-Sky Association Victoria (Australia) (darkskyvic.org)

202312_Impacts of artificial light on wildlife.indd (australasiandarkskyalliance.org)

national-light-pollution-guidelines-wildlife.pdf (dcceew.gov.au)